It has been a whirlwind of a summer getting the Rare Book and Manuscript Library up to full speed in Van Pelt’s new Special Collections Center, but Nicole and I are underway!

The posts to follow will detail our research goals and progress for the summer, and we’d like to formally introduce ourselves. My name is John Baranik. I’ll be a sophomore in the college next year and I am an English major. When I arrived at Penn, I had no idea I’d be working at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library or doing research—I didn’t even know such things existed. A series of classes and influential people and professors, however, led me to where I am now.

In the fall I took a freshman seminar on the Bible with Professor Stallybrass. Not only did our class read texts that were hundreds of years old, but we were able to see and touch many of the actual books themselves that Penn has in its collection. Professor Stallybrass took our class to the Franklin Institute to see the Dead Sea Scrolls, to the Free Library of Philadelphia, and to the Library Company of Philadelphia. I learned of the incredible resources that are available both online—from Penn, The Free Library of Philadelphia, The British Library, Yale’s Beinecke Library, Columbia and Berkeley’s Digital Scriptorium, along with countless others—and in the city of Philadelphia. For my final project, I worked on a section of William Smith‘s commonplace book in which he excerpts and revises the creation scenes in Book VII of Milton’s Paradise Lost. Throughout the semester our class had studied how small changes to important texts can have huge implications (the Geneva Bible’s translation of Adam and Eve’s coverings to “breeches,” for instance) and I was fascinated by the changes that Smith made to Milton’s work; I wondered what Smith, an Anglican priest meant by his revisions and if there were theological implications to his private writings.

In November I began working at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where I am continuing to work this summer. I am daily humbled by the knowledge and modesty of my co-workers: a dreary day of cataloging can instantly turn into a history lesson where I am learning from a post-baccalaureate or Ph.D candidate. Additionally, I have the privilege of watching leading scholars and professors—from the Rare Book School’s Michael Suarez to Paul Needham from Princeton’s Scheide Library to the globetrotting Roger Chartier—work in the reading room, and many are kind enough to share about their research.

In the spring semester, I took a writing seminar, “Shakespeare and Adaptation,” with Claire Bourne. At the time Claire was just finishing her dissertation, “‘A Play and No Play’: Printing the Performance in Early Modern England,” and I was thrilled to have another teacher of an English class that was actively pursuing research in the History of the Material Text. Our class read Margaret Jane Kidnie’s Shakespeare and the Problem of Adaptation, which addressed problems of authenticity and textual multiplicity in Shakespeare. Intrigued by the different trends in English scholarship bent on determining “authentic” Shakespeare, I worked with Claire on the shift in English scholarship from early twentieth century New Bibliography led by W.W. Greg, R.B. McKerrow, A.W. Pollard, John Dover Wilson, and others to the late twentieth century History of the Book movement led by scholars like Randall McLeod and Penn’s own Peter Stallybrass and Margreta de Grazia. At the end of the term, our class took an incredible trip to the Rare Book and Manuscript Library to see some early printed Shakespeare: the First Folio, a number of early quartos, and even Thomas Bowdler‘s “Family Shakespeare. ” As in the fall, I was struck by seeing and touching the actual books—being able to flip through and run my hand over the physical object helped me to understand the scholarship that I had studied.

In addition to Claire’s class, I took another class taught by Professor Stallybrass and Roger Chartier on Printing, Writing, and Reading in Early Modern Europe. In this class, as in Stallybrass’s fall class on the Bible, each classic work that was studied was accompanied by a collection of different editions of the book. In this way, our class could trace the book—whether it was Castiglione, Las Casas, Montaigne, or Richardson—as it was translated and appropriated to different cultures, physically and textually growing and shrinking as it was printed across cultural and political borders. My research in this class involved a final project on the manuscript of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, a document spanning over 18 years and 200 pages. Heavily correcting his manuscript, Franklin blotted, scribbled, and crossed out thousands of words, writing revisions in the facing column and in between the lines. Using an incredible digitized copy from the Huntington Library, I worked together with my friend and roommate Ben Notkin to study the errata: our aim was to look behind the crossed-out and blotted text and try to understand Franklin’s revisions. Additionally, upon discovering revisions with Professor Stallybrass in a hand that looked very unlike Franklin’s, Ben and I put together over 1,000 images from the manuscript to make an alphabet of Franklin’s handwriting over the period in which he produced his autobiography. We then compared this against suspect revisions in the manuscript.

Intermittently, I had been attending the weekly Seminar on the History of the Material Text, where I was able to hear scholars like David Scott Kastan (whose edition of Paradise Lost I read), Roger Chartier, and even the Rare Book and Manuscript Library‘s own John Pollack present on their work. I enjoyed listening to the dialogue and trying to apply the skills and knowledge from my classes to the novel research I was encountering.

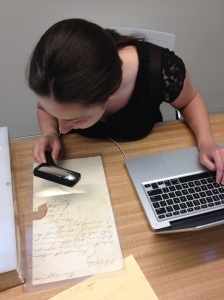

After such a year as an English major, I knew that I wanted to work at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library and that I would enjoy doing primary source research on figures in Philadelphia. My interests converged with Nicole’s and, under the guidance of Professor Stallybrass, we officially formed the Penn Manuscript Collective, a collaborative initiative between Professor Stallybrass and undergraduates with the support and supervision of Will Noel, director of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies. With help from John Pollack, public services specialist and 6th floor hero, Nicole and I drafted a proposal for a summer project and were blessed to receive summer funding from CURF. Enter “Music Printing and Publishing Culture in Early Philadelphia.” This project will study the interactions between printing and music in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Philadelphia to coincide with Penn’s upcoming Year of Sound. It will be the first research project of the Penn Manuscript Collective. Utilizing the materials in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s Keffer Collection of Sheet Music, this project will examine the content, context, culture, and technology of music publishing in this early period of Philadelphia’s history, posting work online in order to make the materials of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library more accessible to the Penn community and researchers at large. At the moment, we are working on some letters that are part of the John Rowe Parker Correspondence. Parker was proprietor of the Franklin Music Warehouse, the largest music distributor in the United States between 1817 and 1821, and this week Nicole and I are transcribing and digitizing the letters of his correspondence with two Philadelphia music publishers, George Willig and Benjamin Carr.

Excellent post, with a great romp through digital resources. Sounds like you’ve got great initiative and a fun concept to cut your teeth on.

Pingback: my4 | See what's possible at a research university.

Pingback: And we’re off! |